Duke of Aquitaine

This article possibly contains original research. (May 2023) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

The duke of Aquitaine (Occitan: Duc d'Aquitània, French: Duc d'Aquitaine, IPA: [dyk dakitɛn]) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As successor states of the Visigothic Kingdom (418–721), Aquitania (Aquitaine) and Languedoc (Toulouse) inherited both Visigothic law and Roman Law, which together allowed women more rights than their contemporaries would enjoy until the 20th century. Particularly under the Liber Judiciorum as codified in 642/643 and expanded by the Code of Recceswinth in 653, women could inherit land and titles and manage their holdings independently from their husbands or male relations, dispose of their property in legal wills if they had no heirs, represent themselves and bear witness in court from the age of 14, and arrange for their own marriages after the age of 20.[1] As a consequence, male-preference primogeniture was the practiced succession law for the nobility.

Coronation

[edit]The Merovingian kings and dukes of Aquitaine used Toulouse as their capital.[citation needed] The Carolingian kings used different capitals situated farther north. In 765, Pepin the Short bestowed the captured golden banner of the Aquitainian duke, Waiffre, on the Abbey of Saint Martial in Limoges.[citation needed] Pepin I of Aquitaine was buried in Poitiers. Charles the Child was crowned at Limoges and buried at Bourges.[citation needed] When Aquitaine briefly asserted its independence after the death of Charles the Fat, it was Ranulf II of Poitou who took the royal title.[citation needed] In the late tenth century, Louis the Indolent was crowned at Brioude.[citation needed]

The Aquitainian ducal coronation procedure is preserved in a late twelfth-century ordo (formula) from Saint-Étienne in Limoges, based on an earlier Romano-German ordo. In the early thirteenth century a commentary was added to this ordo, which emphasised Limoges as the capital of Aquitaine. The ordo indicated that the duke received a silk mantle, coronet, banner, sword, spurs, and the ring of Saint Valerie.[citation needed]

Visigothic dukes

[edit]Dukes of Aquitaine under Frankish kings

[edit]Merovingian kings are in boldface.

- Chram (555–560)

- Desiderius (583–587, jointly with Bladast)

- Bladast (583–587, jointly with Desiderius)

- Gundoald (584/585)

- Austrovald (587–589)

- Sereus (589–592)

- Chlothar II (592–629)

- Charibert II (629–632)

- Chilperic (632)

- Boggis (632–660)

- Felix (660–670)

- Lupus I (670–676)

- Odo the Great (688–735), his reign commenced perhaps as late as 692, 700, or 715, unclear parentage

- Hunald I (735–745), son of Odo the Great, abdicated to a monastery

- Waifer (745–768), son of Hunald I

- Hunald II (768–769), probably son of Waifer

- Lupo II (768–781), Duke of Gascony, opposed Charlemagne's rule and Hunald's relatives.

Direct rule of Carolingian kings

[edit]Restored dukes of Aquitaine under Frankish kings

[edit]The Carolingian kings again appointed Dukes of Aquitaine, first in 852, and again since 866.[citation needed] Later, this duchy was also called Guyenne.[citation needed]

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids)

[edit]| Name | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death | King of the Franks (reign) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranulph I 852[a] – 866 |

820 | Adeltrude of Maine 3 children |

866 | Charles the Bald 843–877) |

| Ranulph II[b] 887 – 890 |

850 | N/A | 5 August 890 | Charles the Fat (881-888) Odo (888–898) |

House of Auvergne

[edit]The following were also Count of Auvergne.

| Name | Portrait | Birth | Death | King of the Franks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I the Pious (893–918) |

|

22 March 875 | 6 July 918 (aged 43) | Odo (888–898) Charles the Simple (898–922) Charles the Simple (898–922) Robert I (922–923) Rudolph (923–936) |

| William II the Younger[c] (918–926) |

12 December 926 | |||

| Acfred[d] (926–927) |

927 |

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids) restored (927–932)

[edit]- Ebalus the Bastard (also called Manzer) (927–932)), illegitimate son of Ranulph II and distant cousin of Acfred, also Count of Poitiers and Auvergne.

House of Rouergue

[edit]- Raymond I Pons (932–936)

- Raymond II (936–955)

House of Capet

[edit]- Hugh the Great (955–962)

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids) restored (962–1152)

[edit]- William III Towhead (962–963), son of Ebalus, also Count of Poitiers and Auvergne.

- William IV Iron Arm (963–995), son of William III, also Count of Poitiers.

- William V the Great (995–1030), son of William IV, also Count of Poitiers.

- William VI the Fat (1030–1038), first son of William V, also Count of Poitiers.

- Odo (1038–1039), second son of William V, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William VII the Eagle (1039–1058), third son of William V, also Count of Poitiers.

- William VIII (1058–1086), fourth son of William V, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William IX the Troubadour (or the Younger) (1086–1127), son of William VIII, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William X the Saint (1127–1137), son of William IX, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137–1204), daughter of William X, also Countess of Poitiers and Duchess of Gascony, married the kings of France and England in succession.

- Louis the Younger (1137–1152), also King of France, duke in right of his wife.

From 1152, the Duchy of Aquitaine was held by the Plantagenets, who also ruled England as independent monarchs and held other territories in France by separate inheritance (see Plantagenet Empire). The Plantagenets were often more powerful than the kings of France, and their reluctance to do homage to the kings of France for their lands in France was one of the major sources of conflict in medieval Western Europe.

House of Plantagenet

[edit]| Name | Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death | King of France |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry I[e] Henry Curtmantle 18 May 1152[f] – 6 July 1189 (37 years, 50 days) |

|

|

5 March 1133 Le Mans Son of Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou and Matilda |

Eleanor of Aquitaine Bordeaux Cathedral 18 May 1152 8 children |

6 July 1189 Chinon Aged 56[g] |

Louis VII (1137-1180) |

| Philip II (1180-1223) | ||||||

| Richard I[h] Richard the Lionheart 3 September 1189[i] – 6 April 1199 (9 years, 216 days) |

|

1198-1340 |

8 September 1157 Beaumont Palace Son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine |

Berengaria of Navarre Limassol 12 May 1191 No children |

6 April 1199 Châlus Shot by a quarrel aged 41[j] | |

| John[k] John Lackland 27 May 1199[l] – 19 October 1216 (17 years, 146 days) |

|

24 December 1166 Beaumont Palace Son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine |

(1) Isabel of Gloucester Marlborough Castle 29 August 1189 No children (2) Isabella of Angoulême Bordeaux Cathedral 24 August 1200 5 children |

19 October 1216 Newark-on-Trent Aged 49[m] | ||

| Henry II[3] Henry III of England 28 October 1216[n] – 16 November 1272 (56 years, 20 days) |

|

1 October 1207 Winchester Castle Son of John and Isabella of Angoulême |

Eleanor of Provence Canterbury Cathedral 14 January 1236 5 children |

16 November 1272 Westminster Palace Aged 65 | ||

| Louis VIII (1223-1226) | ||||||

| Louis IX (1226-1270) | ||||||

| Philip III "the Bold" (1270-1285) | ||||||

| Edward I[4] Edward Longshanks 20 November 1272[o] – 7 July 1307 (34 years, 230 days) |

|

17 June 1239 Palace of Westminster Son of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence |

(1) Eleanor of Castile Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas 18 October 1254 16 children (2) Margaret of France Canterbury Cathedral 10 September 1299 3 children |

7 July 1307 Burgh by Sands Aged 68 | ||

| Philip IV the Fair (1285-1314) | ||||||

| Edward II[5] Edward of Caernarfon 8 July 1307[p] – 1325[q] (18 years, 1 day) |

|

25 April 1284 Caernarfon Castle Son of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile |

Isabella of France Boulogne Cathedral 24 January 1308 4 children |

21 September 1327 Berkeley Castle Murdered aged 43[r] | ||

| Louis X "the Quarreller" (1314-1316) | ||||||

| John I "the Posthumous" (4 days in 1316) | ||||||

| Philip V "the Tall" (1316-1322) | ||||||

| Charles IV "the Fair" (1322-1328) | ||||||

| Edward III[7] Edward of Windsor 1325[s] – 24 October 1360[t] (35 years, 274 days) |

|

13 November 1312 Windsor Castle Son of Edward II and Isabella of France |

Philippa of Hainault York Minster 25 January 1328 14 children |

21 June 1377 Sheen Palace Aged 64 | ||

1340–1360, from 1369 |

Philip VI "the Fortunate" (1328-1350)[u] | |||||

1360–1369 |

John II "the Good" (1350-1364)[u] |

Plantagenet rulers of Aquitaine

[edit]In 1337, King Philip VI of France reclaimed the fief of Aquitaine from Edward III, King of England.[9] Edward in turn claimed the title of King of France, by right of his descent from his maternal grandfather King Philip IV of France. This triggered the Hundred Years' War, in which both the Plantagenets and the House of Valois claimed supremacy over Aquitaine.

| Name | Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward III Edward of Windsor 1337-1360 |

|

Until 1340, 1360–1369  1340–1360, from 1369 |

13 November 1312 Windsor Castle Son of Edward II and Isabella of France |

Philippa of Hainault York Minster 25 January 1328 14 children |

21 June 1377 Sheen Palace Aged 64 |

Lord of Aquitaine (1360-1369)

[edit]In 1360, both sides signed the Treaty of Brétigny, in which Edward renounced the French crown but remained sovereign Lord of Aquitaine (rather than merely duke).[10] However, when the treaty was broken in 1369, both these English claims and the war resumed.

| Name | Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward III Edward of Windsor 1337-1360 |

|

1360–1369 |

13 November 1312 Windsor Castle Son of Edward II and Isabella of France |

Philippa of Hainault York Minster 25 January 1328 14 children |

21 June 1377 Sheen Palace Aged 64 |

Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony (1362-1372)

[edit]In 1362, King Edward III, as Lord of Aquitaine, made his eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales, Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony.[11]

| Name | Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward, Prince of Wales 19 July 1362 - 6 October 1372 10 years, 79 days |

|

|

15 June 1330 Woodstock Palace Son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault 2 children |

Joan of Kent 1361 |

8 June 1376 Westminster Palace Aged 45 |

On 6 October 1372, Prince Edward (who had returned to England the previous year) resigned the Principality of Aquitaine and Gascony, stating that the revenues he earned from Aquitaine were no longer sufficient to cover his expenses.[12] Thus, King Edward III, his father, resumed his title as Duke of Aquitaine.

Duke of Aquitaine (1372-1453)

[edit]| Name | Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward III[13] Edward of Windsor 1372 – 21 June 1377 (5 years) |

|

From 1369 |

13 November 1312 Windsor Castle Son of Edward II and Isabella of France |

Philippa of Hainault York Minster 25 January 1328 14 children |

21 June 1377 Sheen Palace Aged 64 |

| Richard II[14] Richard of Bordeaux 22 June 1377[v] – 1390 (13 years) |

|

6 January 1367 Archbishop's Palace of Bordeaux Son of Edward the Black Prince and Joan of Kent |

(1) Anne of Bohemia 14 January 1382 Westminster Abbey No children (2) Isabella of Valois Church of St. Nicholas, Calais 4 November 1396 No children |

14 February 1400 Pontefract Castle Aged 33 | |

| John II John of Gaunt[w][x] 1390 - 1399 9 years |

|

|

6 March 1340 Ghent son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault |

Blanche of Lancaster 19 May 1359 – 12 September 1368 8 children Constance of Castile 21 September 1371 – 24 March 1394 2 children Katherine Swynford 13 January 1396 4 children |

3 February 1399 Leicester Castle aged 58 |

| Richard II[y] Richard of Bordeaux 3 February – 30 September 1399 (239 days) |

|

1395–1399 |

6 January 1367 Archbishop's Palace of Bordeaux Son of Edward the Black Prince and Joan of Kent |

(1) Anne of Bohemia 14 January 1382 Westminster Abbey No children (2) Isabella of Valois Church of St. Nicholas, Calais 4 November 1396 No children |

14 February 1400 Pontefract Castle Aged 33 |

| Henry III of Aquitaine Henry IV of England 30 September 1399[z] – c. 1400 |

|

until 1406 |

c. April 1367 Bolingbroke Castle Son of John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster |

(1) Mary de Bohun Arundel Castle 27 July 1380 6 children (2) Joanna of Navarre Winchester Cathedral 7 February 1403 No children |

20 March 1413 Westminster Abbey Aged 45 |

| Henry IV of Aquitaine Henry of Monmouth[aa] c. 1400– 31 August 1422 (22 years) |

|

until 1406  1406-1413  from 1413 |

16 September 1386 Monmouth Castle Son of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun |

Catherine of Valois Troyes Cathedral 2 June 1420 1 son |

31 August 1422 Château de Vincennes Aged 35 |

| Henry VI 1 September 1422[ab] – 1453[ac] (31 years) |

|

|

6 December 1421 Windsor Castle Son of Henry V and Catherine of Valois |

Margaret of Anjou Titchfield Abbey 22 April 1445 1 son |

21 May 1471 Tower of London Allegedly murdered aged 49 |

| Duchy of Aquitaine annexed into the Kingdom of France, title abolished | |||||

Valois and Bourbon dukes of Aquitaine

[edit]The Valois kings of France, claiming supremacy over Aquitaine, granted the title of duke to their heirs, the Dauphins.

- John II (1345–1350), son of Philip VI of France, acceded in 1350 as King of France.

- Charles, Dauphin of France, Duke of Guyenne (1392?–1401), son of Charles VI of France, Dauphin.

- Louis (1401–1415), son of Charles VI of France, Dauphin.

With the end of the Hundred Years' War, Aquitaine returned under direct rule of the king of France and remained in the possession of the king. Only occasionally was the duchy or the title of duke granted to another member of the dynasty.

- Charles, Duc de Berry (1469–1472), son of Charles VII of France.

- Xavier (1753–1754), second son of Louis, Dauphin of France.

The Infante Jaime, Duke of Segovia, son of Alfonso XIII of Spain, was one of the Legitimist pretenders to the French throne; as such he named his son, Gonzalo, Duke of Aquitaine (1972–2000); Gonzalo had no legitimate children.

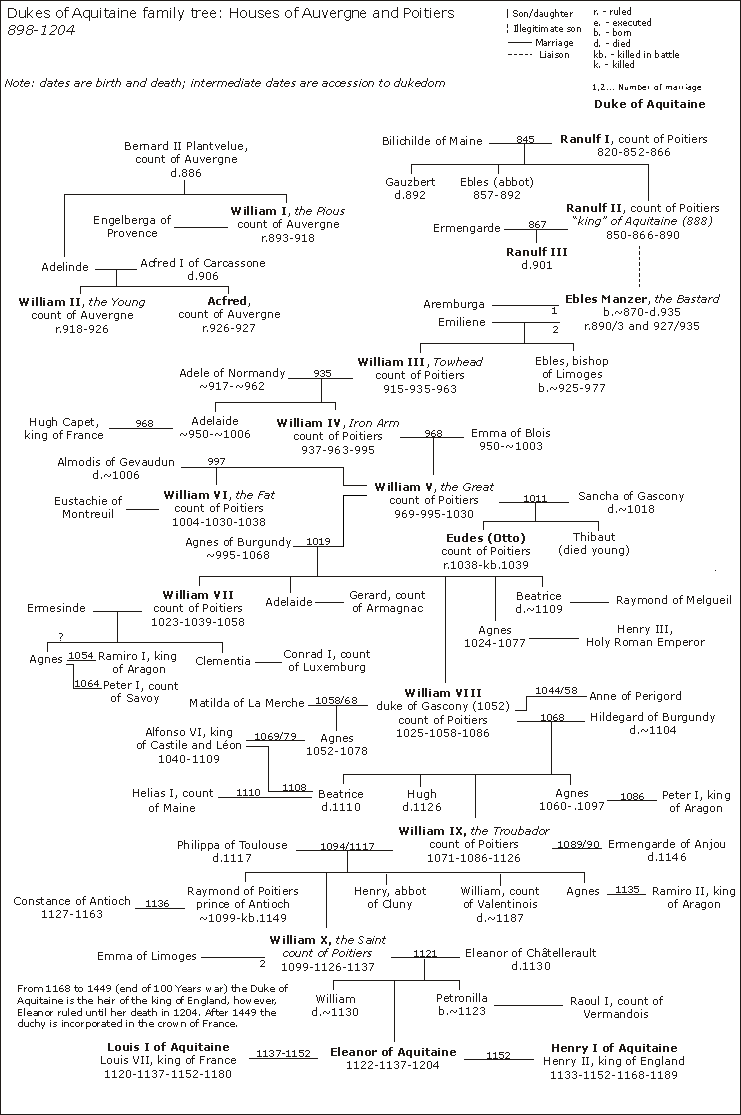

Family tree

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Count of Poitiers from 835, Duke of Aquitaine from 852

- ^ Son of Ranulf I, also Count of Poitiers, called himself King of Aquitaine from 888 until his death.

- ^ nephew of William I

- ^ brother of William II

- ^ Duke of Aquitaine by right of his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

- ^ Henry Curmantle was crowned as King Henry II of England on 19 December 1154 with his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

- ^ Henry II was buried at Fontevraud Abbey.

- ^ Ruled alongside his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who acted as regent for the Duchy while he was on crusade – a position he resumed on his return to Europe.

- ^ Richard I was crowned on 3 September 1189.

- ^ Richard I was buried at Rouen Cathedral. His body currently lies at Fontevraud Abbey.

- ^ Ruled alongside his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, until her death in 1204; afterwards, sole duke of Aquitaine.

- ^ John was crowned on 27 May 1199.

- ^ John was buried at Worcester Cathedral.

- ^ Henry III was crowned on 28 October 1216.

- ^ Edward I was crowned on 19 August 1274 with Queen Eleanor.

- ^ Edward II was crowned on 25 February 1308 with Queen Isabella.

- ^ Edward II continued as King of England until 20 January 1325

- ^ The date of Edward II's death is disputed by historian Ian Mortimer, who argues that he may not have been murdered, but held imprisoned in Europe for several more years.[6]

- ^ Edward of Windsor, while still heir to the throne, was appointed Duke of Aquitaine by his father, King Edward II of England.[8] After the king was overthrown by the Parliament of 1327, Edward III was proclaimed the new King of England on 25 January 1327, and crowned on 1 February 1327.

- ^ On 24 May 1337, Philip VI of France confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine from Edward III, beginning the Hundred Years' War.[9] Regardless, Edward III continued to title himself Duke of Aquitaine, and responded by claiming the throne of France for himself. Edward continued to use the titles of King of England and France and Duke of Aquitaine until the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, when Edward renounced these titles in exchange for recognition as sovereign Lord of Aquitaine.

- ^ a b Philip VI and John II's position as King of France was disputed by King Edward III of England from 1340 until 1360.

- ^ Richard II was crowned on 16 July 1377.

- ^ In 1390, King Richard II, son of Edward the Black Prince, appointed his uncle John of Gaunt Duke of Aquitaine. This grant expired upon the Duke's death, and the dukedom reverted to the Crown. Regardless, due to Henry IV's seizure of the crown, he still came into possession of the dukedom. [15] [better source needed]

- ^ Also Duke of Lancaster (1362), Earl of Leicester, Earl of Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Baron of Halton (1361). Formerly Earl of Richmond from 1342 until 1372.

- ^ Second tenure

- ^ Henry IV was crowned on 13 October 1399.

- ^ Henry, Prince of Wales to 1413, Henry V of England afterwards

- ^ Henry VI was crowned on 6 November 1429.

- ^ Effectively lost control of Aquitaine after the end of the Hundred Year's War

References

[edit]- ^ Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane; A History of Women: Book II Silences of the Middle Ages, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. 1992, 2000 (5th printing). Chapter 6, "Women in the Fifth to the Tenth Century" by Suzanne Fonay Wemple, pg 74. According to Wemple, Visigothic women of Spain and the Aquitaine could inherit land and title and manage it independently of their husbands, and dispose of it as they saw fit if they had no heirs, and represent themselves in court, appear as witnesses (by the age of 14), and arrange their own marriages by the age of twenty

- ^ Lemovicensis, Ruricius; Limoges), Ruricius I. (Bishop of (1999). Ruricius of Limoges and Friends: A Collection of Letters from Visigothic Gaul. Liverpool University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780853237037.

- ^ "Henry III (r. 1216–1272)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 37.

- ^ "Edward I 'Longshanks' (r. 1272–1307)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 38.

- ^ "Edward II (r. 1307–1327)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Mortimer, Ian (2008). The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-952709-1.

- ^ "Edward III (r. 1327–1377)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Mortimer 2006, p. 39.

- ^ a b Previté-Orton 1978, pp. 873–876.

- ^ Curry 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Hunt 1889, p. 96 cites Fœdera, iii. 667.

- ^ Hunt 1889, p. 100 cites Rot. Parl. ii. 310; Hallam, Const Hist, iii. 47.

- ^ "Edward III (r. 1327–1377)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 39.

- ^ "Richard II (r. 1377–1399)". royal.gov.uk. 2016-01-12. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.; Fryde 1996, p. 40.

- ^ "Would the grant of Aquitaine to John of Gaunt in 1399 have been inherited by Henry Bolingbroke had the latter not been exiled by Richard II?" at researchgate.net

Bibliography

[edit]- Curry, Anne (2003). The Hundred Years War. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fryde, Edmund B., ed. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd ed.). Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- Mortimer, Ian (2006). The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-2240-7301-X.

- Previté-Orton, C. (1978). The shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5212-0963-2.

Attribution

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hunt, William (1889), "Edward the Black Prince", in Stephen, Leslie (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 17, London: Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 90–101

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hunt, William (1889), "Edward the Black Prince", in Stephen, Leslie (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 17, London: Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 90–101